Media studies often assumes a naive attitude toward its objects of study, taking concepts like “communication,” “circulation,” and “access” as ideals. In “Critically Engineered Wireless Politics,” Jussi Parikka challenges this common attitude through an engagement with contemporary media theory and an extended discussion of a 2011 exhibition at the Transmediale by the Berlin-based Weise7 group.

The aim of Parikka’s article is partly to demonstrate an alternative, more critical stance toward media, which he designates with the umbrella term “evil media.” In the same turn, Parikka prefers the particular term “critical engineering” to the more common “hacktivism” due to the former’s resonance with the main concerns of modernity (3). This critical, engineering stance toward evil media requires shifting our attention from “the idealistic discourse of media as communication” to “interruption, hijacking and the engineered parasitical event” (2). In contrast to what might be termed the “benevolent media” of communication studies, evil media designates a field of opacity, “trickery, deception, and manipulation” (ibid.). Significantly, the field of evil media is not exclusively the domain of media theory and written texts, but also encompasses engineering practices, such as writing code, creating devices, and intervening in network services. At one point, Parikka even refers to these practices, just as Brian Holmes might, “as an exercise in the psychogeography of code: it is to do with mapping the architectures in which mind and body control work” (13).

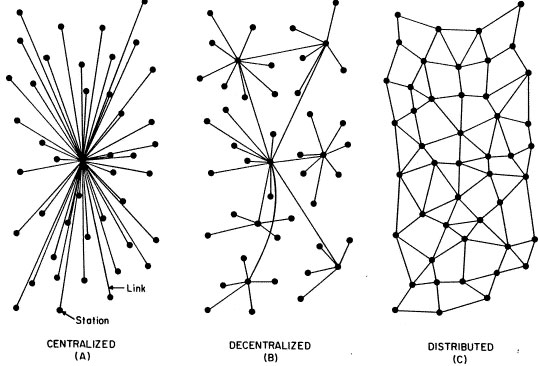

Interestingly, the “wireless politics” under discussion here are framed as a part of the field of “network and platform politics” (4; my emphasis). Conceiving of wireless as a “platform” means taking into account hardware, software, and networking protocols. While the theory of affordances would have it that wireless networks are “for” creating real-time communications, the critical engineering approach to wireless networks would highlight the disjunctures and gaps inherent in establishing these connections. To establish the significance of this alternative approach to wireless networks, Parikka paraphrases Adrian Mackenzie’s work on “wirelessness:” “Despite that [i.e., people’s lack of interest in, or experience of, wireless technology], their sensations of connection, their awareness of service availability, and their sometimes conscious preoccupation with connecting their wireless devices via service agreements or other devices all derive from the handling of conjunctive relations in data streams implemented in wireless signal processing chips” (6-7). Hacking, or “critically engineering,” wireless devices can make these processes more tangible.

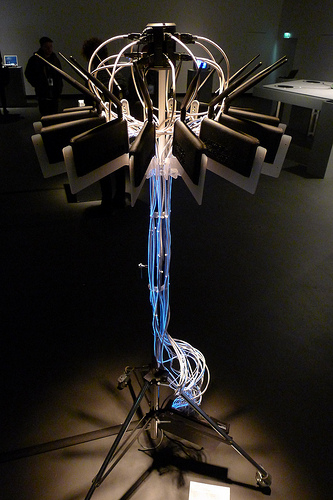

Several Weise7 projects focus explicitly on re-engineering wireless technology (e.g., “Packetbrücke,” Vasiliev’s “Netless,” a wireless book, and the group’s “Networkshop”). In doing so, they attempt to create an experience of imperceptible phenomena, “an imperceptibility that connects to the ontological regime of wireless communication, part of the discourse of wirelessness since the 19th century. Imperceptibility relates to the sphere of secrecy and paranoia” (12-13). Critical engineering “exposes how infrastructure is in most cases less stable than it seems. It also leaks data on many fronts, intervening in negotiations of public and private, also more broadly in wireless infrastructures across cities” (15). A critically engineered wireless politics would expose the invisible operations that inform network infrastructures, just as critical theory exposes the invisible forces of society, history, and ideology that constitute culture.

Source

Parikka, Jussi. “Critically Engineered Wireless Politics.” Culture Machine 14 (2013).